History rarely gives us a break. So have one here and now: Take a deep breath in and out. Relax your shoulders. It is May 1945 and the war is over. The Allies divide the former German Reich into four occupation zones: French, American, British and Soviet. All that is left of the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies is its building.

Chapter 3

The Central Council of Jews

In 1950, the Central Council was in fact only founded on a temporary basis to represent the newly formed communities – at least, until all the Jews had left Germany. The majority initially saw Germany as a stopover, but over the decades it became apparent that some Jews had found a new perspective on life in Germany. Even today, the Central Council continues to strengthen and promote Jewish communities and Jewish life in Germany.

You remember: The building of the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies in the former Artilleriestraße was purpose built. Its open doors were a symbol of spiritual refuge and intellectual resistance. After the war, the building is in the Soviet occupation zone. And that has consequences for the historically significant house.

In West Germany, the Allies are trying to undo Nazi injustice and return looted Jewish property to its rightful owners.

The Soviet military administration in East Germany has no interest in doing this. It regards the confiscated assets of the German Reich as state property which it can dispose of – Nazi loot or not. In accordance with socialist policy, real estate that was seized from Jewish people is also nationalised and given to public institutions.

So it happens that after the war the former building of the Institute is used by the

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the building is handed over to the

So the good news is: the Institute’s building is back in Jewish hands. The tragedy is that Jewish institutions in Germany are dependent on extensive security measures. Its doors therefore remain closed to the general public. A harsh contrast to the Institute’s policy back in the day.

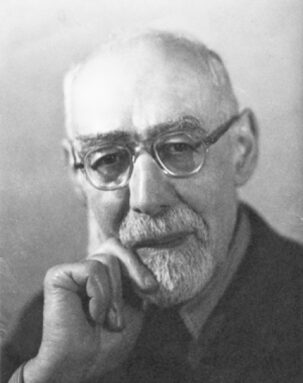

The building in which the Institute was housed from 1907 to 1941. Today it serves as the headquarters of the “Central Council of Jews in Germany” and bears the name of the Institute’s last head: Leo Baeck House.

And the library?

WThe Institute’s cultural heritage, that made it through the war unscathed, is now scattered in all directions. In an attempt to save their own skins, the Nazis leave the books behind. They have not fallen into oblivion. They are sought, recovered and fiercely contested.

This search – does it sound like an adventure you might enjoy?

The original and rightful owner of the library’s books would be the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies. But its closure under duress in 1942 remains final. Individual representatives, including Leo Baeck, the former head of the Institute, as well as several lecturers, declare their interest in the books. But can they really lay claim to them? As individuals, they do not represent the entirety of the Institute – especially since their interests diverge widely. And they are by no means the only ones who are making plans for the remains of the Institute’s library.

There are German libraries, for example, which lack scientific books. The war has left gaps on their shelves that they would like to fill up again. Researchers need the books to pursue their studies. Jewish survivors, in turn, are looking for their property, their private libraries. The Jewish community wants the books to be an important cultural asset of their new political centre, which is going to be established outside of Europe. But where exactly that would be, remains an open question. So there is not just one idea of what should happen to the books. And a wide variety of interest groups set out to find the remaining library holdings.

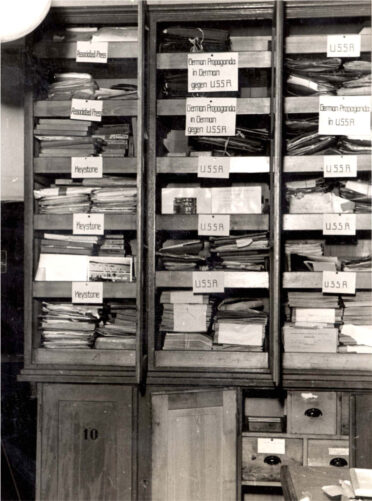

View into a storeroom of the Offenbach Archival Depot. Once they arrive in Offenbach, the recovered books are stored here before being sorted and identified.

The Library of Lost Books

The library you have been exploring for some time now, should never have existed. It bears loss in its name. It is a memorial to remind us of one of the darkest chapters in human history. And it testifies to a fraction of the persecution, resistance, survival and cruelty of the Nazi era. The empty shelves would have shocked Jenny Wilde, librarian of the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies. The library held 60,000 books. About 5,000 of those books have been found all over the world so far. You do the maths and think: that’s too few. Where are the others? There are a few leads we can follow.

Isaiah Rackovsky, one of the OAD staff, identifies and sorts individual leaves of Hebrew prints.

We are sure that we can still find more of the Institute’s books. Significant events, previous recovery sites and tried and tested search strategies can give us clues as to where to look.

So let’s go back a few steps on the timeline and follow the trail of the books.

Click me!

A trail of exciting strategies

Learning from the Americans

After the war, among the Western Allies, the Americans are the ones who lead the systematic search for hidden cultural assets, which are gathered at so-called “central collecting points”. The most important “central collecting point” for books is the “Offenbach Archival Depot” (OAD) near Frankfurt am Main. From here, the books are to be returned to their rightful owners. And within an incredibly short period of time, this happens for large quantities of books.

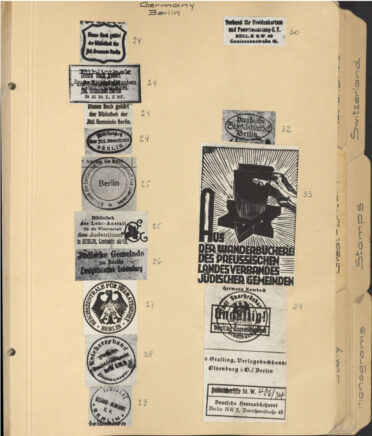

One of the OAD’s methods has proven very successful: the staff take photos of the stamps and bookplates and collect them in a large album, which is divided by countries and owners. The visual comparison makes it possible to quickly identify and classify even foreign-language stamps.

The work of the OAD is of great significance. On the one hand, it recognises the great importance that books hold for the Jewish community: they advance the tradition and the continuation of Jewish culture. On the other hand, the books collected in Offenbach also represent the history of the murder of European Jews: each book reveals something about the history of its owner and the experience of National Socialist destruction. Today, a book can be the only reminder of the person to whom it once belonged. Some books contain dedications that tell us about special occasions. Some complete the portrait of a person.

Between March 1946 and June 1949, around 1.4 million books are returned by the OAD to their rightful owners. Yet books are still left over. Because it is not possible to find out to whom they belong, or because the owners have not survived and the legal succession is unclear. The Institute’s books are also among these “heirless” specimens. Under normal circumstances, there is a law that regulates such cases: If no heir can be found, the property of the deceased is forfeited to the country in which he or she lived. If this were to be applied to the looted books however, the outcome would be grotesque. For then, even after its unconditional surrender, Germany would profit from the mass murder and persecution. This can’t be allowed.

“Even German criminal law of the interwar period stipulated that a murderer can never become the legal owner of the property of the murdered person.” – Memorandum of the Jewish National and University Library (1946)

That is why the

for the heirless cultural property. The American armed forces hand over the remaining books in their possession to this organisation and the JCR distributes them to Jewish educational and cultural institutions in Israel, England, the USA, Central and South America and South Africa.

What lessons can we take away from the Americans and the Offenbach Archival Depot for our search? That the books reveal more than just the written word. That a systematic approach is worthwhile. And that many books have been legitimately scattered all over the world, where they have remained until today

A strong lead has given you an idea and you want to follow it right away? We won’t stop you

“These books were monuments of memory and functioned as symbolic tombstones of the owners who were murdered without a trace.”

Hot on the heels of famous books

The Red Army’s trophy brigades, American restitution organisations, trusts and German libraries: they are all after the books. Working for them, whilst also carrying out their own mission, we can see some familiar faces like Leo Baeck and Ernst Grumach. We also cross paths with the famous philosopher Hannah Arendt. For very few the mission is strictly professional. Many have a personal connection to the books. Come, let’s accompany them for a while!

Wrong tracks

You may be asking yourself: What about the books that were courageously smuggled out of the country during the war? We can follow some of their tracks today. Some lead nowhere. And in some cases, there were even attempts to cover them up…

Nazi-looted property as commodity?

Whether museum, archive or library – almost all institutions have come to realise that they have to research the provenance of their objects and collections to find out whether they contain Nazi-loot. But what should be done when Nazi-loot is put on the market? One view is to buy it at all costs, so that the object can be prevented from disappearing into a private collection and made available to the public instead. On the other hand, such a purchase naturally contributes to someone making money from Nazi-loot. This in turn boosts the demand for objects obtained through crime. Opinions on this issue remain divided.

Alexander Guttmann’s rescue mission

Do you remember? Alexander Guttmann, a Talmud lecturer, had taken the Institute’s 60 most valuable books abroad as part of his private library. But not every rescue story ends in glory. In fact, not much happens to the books once they arrive in the USA. Guttmann keeps them to himself and remains silent. In 1984, the works suddenly turn up at Sotheby’s auction house. The seller wishes to remain anonymous. But the Institute’s stamps in the books are eye catching and the New York Attorney General stops the auction to find the real owner the books. Does the seller even have the right to put them up for auction?

It soon becomes clear that the seller is Alexander Guttmann. Herbert Strauss, a former student and eyewitness at the meeting between Jenny Wilde and her colleagues, is called to testify in the proceedings concerning the books. He confirms the existence of a plan to smuggle the Institute’s most valuable books out of Germany in order to protect them from the Nazis.

Guttmann, on the other hand, claims that the books were given to him as a gift. A generous settlement helps to put the legal dispute to rest. The books are purchased by the Judaica Conservancy Foundation, which is set up specifically for this purpose. It wants to make the books accessible to the public again. In the end, the rescue operation succeeds, albeit in a roundabout way.

If we follow the trail of the books, it also helps us to realise that the story is time and again more convoluted than we would perhaps like it to be. Often, we look in vain for the classic hero or heroine and find real-life entanglements and contradictory narratives instead.

What is your opinion?

Locked away and forgotten?

And now? History reveals itself to be slow and forgetful. The books were fiercely contested. They were handed over to their owners or to trusts. Libraries all over the world have arranged them into their shelves. And then? In the 1960s, the books started to fall into oblivion, they were discarded and disregarded. Are you outraged? Rightly so!

Once again, it is time for resistance!

We have witnessed what the books meant to the people of the Institute. They are an expression of a progressive current of modern Judaism. Of topics that still move us today. They are contemporary testimonies of intellectual resistance to anti-Semitism. They have given comfort, sometimes even hope, to people subjected to forced labour. They were rescued, hidden and protected despite all the dangers. They survived the Holocaust. Unlike many of their owners. They are the legacy of an Institute, that we still want to keep alive today.

The Higher Institute for Jewish Studies has done nothing less than establish the academic study of Jewish history and culture in Germany. A Judaism that is open to new paths in a changing world. The Institute’s influence, perpetuated by its graduates, is today still visible in Jewish schools, educational institutions and synagogues. Its academic findings have shaped modern Jewish thought from theology and philosophy to literature, history and sociology. Some of the most important texts on Judaism of the 20th century were also written by scholars who trained or taught at the Institute. Last but not least, the Institute has preserved Jewish heritage and culture and made them accessible during a time of extreme persecution and extermination. Its books have hardly lost any of their importance.

They are still valuable texts for scholars of Jewish history. In order to make them accessible to the widest possible audience, important sources have been digitised. It does not matter where they are located. Even books whose content is today no longer relevant serve as precious artefacts, as witnesses of their time. They tell of the robbery, of the attempt to appropriate the interpretation of Jewish history. But also of the fierce fight over who was to inherit the legacy of German Jewry after the war.

The end

before

the beginning

The beginning before the end

The well-stocked library of the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies, the work of Jenny Wilde and of the entire staff fell victim to Nazi persecution. Its holdings were scattered around the world. Until today. Until you enter the Library of Lost Books. A name, the library does not want to keep. We have made it our mission to fill its shelves. Because even today we can do something to counter the injustices of National Socialism. Are you with us?

The Library of Lost Books is a virtual collection of books from the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies. Honouring the Institute’s tradition, its doors are open to academic discourse. You can already view over 2,000 books in our library. As you know, this is only a fraction of the Institute’s precious treasure trove of knowledge.

Help us to find more books! Up to this point, you haven’t just been following the history of the Institute. You have learnt to read clues. You’ve learnt how your predecessors made headway by working like detectives. These are big shoes to fill. And we are convinced that you can fill them.