The Association, founded in April 1904, served as an umbrella organisation for Jewish groups in Germany. Its primary mission was to represent all German Jews politically, regardless of their religious affiliations or social strata, to the state and its authorities. The aim was to achieve recognition and legal equality for Jewish people in Germany and to counter antisemitic attacks. During the First World War, the Association organised Jewish military chaplaincy.

During her time at the Association of German Jews, Johanna Nathan not only met Leo Baeck, who would become important in her professional life, but also Paula Glück. Glück, born in 1883, had grown up in an orphanage like Nathan. The women became friends, attending services together on holidays and living together from 1913.

After the dissolution of the Association of German Jews in 1922, Johanna Nathan moved to the Society for the Advancement of the Science of Judaism. Lastly, she worked as a clerk for the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies. One of her tasks was to register the return of borrowed books. Johanna Nathan and Paula Glück were deported to Auschwitz on 12 March 1943 and murdered.

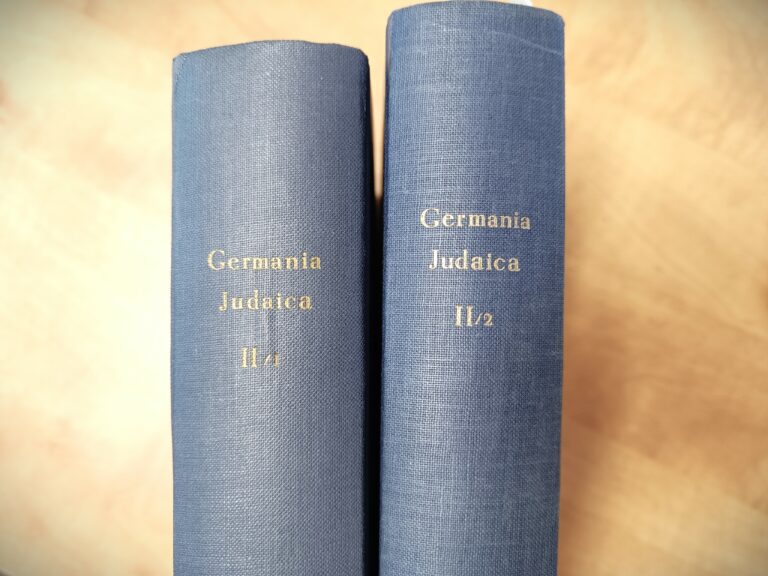

The rescue of Germania Judaica

Though not a single picture of Johanna Nathan has survived, her courageous effort to preserve writings on Jewish history is well-documented – a deed of enormous importance in light of the systematic appropriation of Jewish historiography by the Nazi regime at the same time.

One of the most important foundational works on German-Jewish history is Germania Judaica. The first volume was published between the World Wars; another volume was planned. But then came the November Pogrom, during which the editors’ office was vandalised. All notes and entries for the book were destroyed or confiscated and it seemed as though these extensive preparatory works were irretrievably lost. To everyone’s surprise, however, years later, it was discovered that a significant portion of the articles had been saved by Johanna Nathan. Zvi Avneri described in 1958 how Johanna Nathan saved these valuable notes:

“By November 1938, about 400 articles had been received; then the work was interrupted by the pogroms, resumed after some time, and gradually came to a standstill due to the emigration of the editors, most of the contributors, and the editorial secretary. Miss Ottenheimer ended her life in a concentration camp. Shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, the Society’s office was closed by the Gestapo and all material there confiscated, including the essays written for Germania Judaica edited by Aron Freimann and Adolf Kober. Despite all efforts, it has not been possible to find them to this day. However, most essays (an estimated 80 percent) survived in uncorrected versions, just as they had been sent by the authors or typed at the Society’s offices. It is thanks to Miss Johanna Nathan, the long-time secretary of the Society, that this material was saved; otherwise, it would be impossible to complete Germania Judaica today. Before Eugen Mittwoch, the last chairman of the Society, left Germany, Miss Nathan had the fortunate idea of bringing the essays located in the Society’s office to his home, and that is how they reached London in 1939 along with his library. After Mittwoch’s death, his widow showed the essays to Dr Leo Baeck, who as vice-chairman of the Society had shown great interest in Germania Judaica for many years. He immediately recognised their value, and with his consent, all the material was deposited at the Jewish Historical General Archives in Jerusalem in 1954. The Leo Baeck Institute then took over the completion of the work and commissioned the author of these lines with the preparatory work. In doing so, the Institute has declared itself, in a manner of speaking, the heir of the Society to Advance Jewish Studies (Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaft des Judentums) and is taking on the associated obligation to bring its final work to fruition.” (Source: Bulletin of the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem (1958), issue 2–3, p. 115)

Thanks to Johanna Nathan’s decisive intervention, the long-planned book was eventually published, albeit thirty years later.

“The Jewish work of that period was unique. It could be described as a legal form of underground work, always within the law, yet shrouded in secrecy. Such work could only be accomplished by people upon whom you could absolutely depend, depend on their loyalty and resolve. Above all, that meant the secretaries, to use their technical title. If memories are to be reawakened here and in Germany, two names should be invoked, Jewish lives in Germany: Paula Glück and Johanna Nathan, two orphan girls, one from Pomerania, the other from Posen, raised together in a Berlin orphanage. What immense contributions to Jewish work those two weak women carried on their shoulders during those terrible years. They should never be forgotten either.“