Wait, I’ll turn on the light. Times are dark enough. Don’t worry, you’re safe. Unfortunately, that doesn’t apply to everyone at the Institute. Something is brewing. And the Institute is caught in the eye of the storm. The Jewish population is threatened with persecution, exclusion and systematic murder. The people you have met up to this point are fighting with all their might against the oppression and deprivation of rights inflicted by the National Socialists. And ask themselves questions whose answers are dictated by sheer necessity, such as: Would you risk your life to save a book?

Chapter 2

The beginning of the end

E

It’s 1933, and you know what that means: the National Socialists have seized power. Nazi anti-Jewish laws subject the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies to arbitrary harassment. The Institute improvises. It sounds the alarm. But the amazing thing is: it exists. And it becomes a place of refuge for Jewish students and lecturers from all over Europe.

“Even if this had not been the most precarious human situation I was ever to experience, I would have remembered these men and women who, in the midst of decay, danger and disaster, created an oasis of stability in their lectures, seminars and tutorials.”

(Herbert A. Strauss, former student of the Institute)

National Socialist anti-Jewish policies deliberately force Jews from public life, including from educational institutions. With the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” and the “Law against the Overcrowding of German Schools and Universities”, Jewish people are barred from teaching and studying at state institutions. But the doors of the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies are open to them. This attracts lecturers and students from a wide range of disciplines – and inevitably expands the range of courses offered at the Institute.

But who actually thinks about teaching or studying at times like these? For Jewish lecturers, the Institute remains one of the few opportunities to earn money. For some time, their employment even offers protection from

There are also other reasons that make studying so appealing: many Jews do not believe in a future in Germany and sense the danger. They want to get a degree and acquire qualifications that could be useful to them in a new homeland. Many take courses to directly prepare themselves for their emigration. But the Institute also becomes a spiritual refuge:

“Of course we were not naïve, we knew about the danger that surrounded us and was constantly lurking, but we still lived as if on an island. I mean, this experience shows what Jewish life, Jewish learning has always meant: to survive despite everything, taking refuge in the world of teaching. […] That’s why, despite perceiving the world and its horrors, our refuge, the Institute, remained more important. That’s where we were at home and that’s where we were ultimately safe.”

After the

A year later, the number of students is down to about 20 to 25. Leo Baeck turns down all opportunities to leave the country and continues to run the Institute. Despite the circumstances, he succeeds in recruiting new teaching staff, including retired scholars and rabbis from Jewish communities in Berlin. Part-time teachers offer so-called “practical courses”, including Public Speaking, Spanish, English, Modern Hebrew Texts, Jewish Social Work, Gymnastics.

The last people at the university include

And you! You are there! And even today you can show solidarity with the people of the Institute.

The last summer semester is solemnly opened on 29 April 1942. It is not completed. On 19 July 1942, the Institute is forced to close for good. A heavy blow for Leo Baeck:

“When he had to announce that the Institute would have to close, it was the only time he lost his temper in public.”

(Herbert A. Strauss, 1999)

The Institute’s course catalogue for the summer semester of 1942. Leo Baeck offers courses on Tuesday and Friday mornings, Julius Lewkowitz on Wednesday evening.

An incomplete chronology of systematic discrimination

And now?

In the end, the Nazis shut down the Institute – so, what is there left to talk about then? We talk about what the Nazis would like to keep quiet. We tell of courageous resistance and ingenious rescue operations. We tell of escapes into the world of books when one’s own world is in flames. We tell of not surrendering the writing of history to the Nazis. Are you with us?

May 1933: More than a hundred thousand people take part in a protest march against the Nazis in New York.

The contradictions of Nazi ideology

We remember: At the end of the 19th century and well into the 20th century, German state universities did not allow the study of Judaism. As a result, the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies was founded as a private institution with the help of donations. Under National Socialism, however, interest in Jewish history grows exponentially – albeit with the aim of substantiating anti-Jewish legislation with supposedly scientific evidence. It’s about the power of definition. About having the last word on Jewish history, at a time when Germany seems determined to put an end to it in.

Anti-Jewish “Jewish Studies”

…are one of many Nazi pipe dreams. They are supposed to scientifically prove the “objectivity” and the “validity” of Nazi ideology. Numerous National Socialist research institutions devote themselves to anti-Jewish science and engage with the history and culture of Judaism in an explicitly anti-Semitic way. These included, for example, the “Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question”, which belonged to the

“The reduction of Jews to objects of research was the declared aim of all these undertakings. A supposedly Jewish-dominated view of German-Jewish history was to be replaced by a non-Jewish German perspective.”(Nicolas Berg & Dirk Rupnow 2006)

The system rewards eagerness: Those who conduct “Jewish studies” have fast promotion prospects. What falls under this research category remains a matter of interpretation. The common factor is the legitimisation of anti-Jewish policies. Young academics in this bizarre “branch of research” are enthusiastic about being able to exert power through intellectual work. They wield influence on police practice and not least on the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question”.

Intellectual resistance

Jewish historians courageously oppose the propaganda onslaught. They fight against a dangerous, overbearing force. Their weapon is their intellect.

You and your intellect want to fight the Nazis too?

One example among many: One of the most successful “Jewish researchers” under National Socialism, Wilhelm Grau, promotes the exclusion of German Jews from German history and historical scholarship. He also does this in his book “Anti-Semitism in the Late Middle Ages”. Ismar Elbogen – we already know him as one of the Institute’s lecturers – counters with a scathing review. The author’s problem, he says, is that he has the answer ready before the question.

Grau later retaliates with a poor assessment of Elbogen’s new publication. Elbogen’s emigration in 1938 puts an end to the dispute.

What may seem like a normal scientific debate is in fact deadly serious. In 1935, the power imbalance between Jewish and non-Jewish academics is vast, with unforeseeable consequences for those who disagree.

The book theft

At a time when public discourse isn’t shaped by comment sections, but by books, the question as to who writes them, owns them, or is allowed to consult them, becomes crucial. Where there are books, there is the authority to interpret history. It isn’t surprising that the Reich Security Main Office tries to seize as many Jewish libraries as possible. Without any evidence to the contrary, the Nazis can spread their own version of history.

In 1939, the Reich Security Main Office begins to build up its so-called “Jewish Library”. The

The “11th Decree to the Reich Citizenship Law” of 1941 justifies their actions: according to the law, the German Reich is entitled to the assets of Jews who have fled Germany. This also applies to deported Jews – the official argument is that “by crossing the borders of the Reich, they transferred their domicile or habitual residence abroad.” Instead of “robbery”, there is talk of “safekeeping” of books. Keeping them safe from “wild looting”, that is. By September 1939, all important Jewish libraries – both public and private – are moved to Berlin.

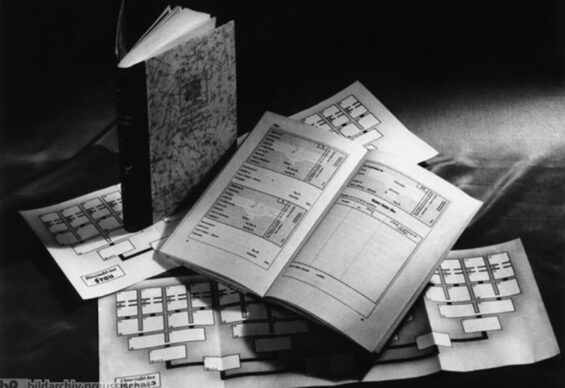

The stamp of the library of the so-called Reich Institute for the History of the New Germany.

Jewish Question Research Department of the Reich Institute for the History of the New Germany

Nazis sift through the books looted from the library of the Institute for Sexual Science founded by Magnus Hirschfeld. Part of the stolen books were publicly burned in May 1933. Another part was retained and redistributed.

The steadfastness of the Institute’s library

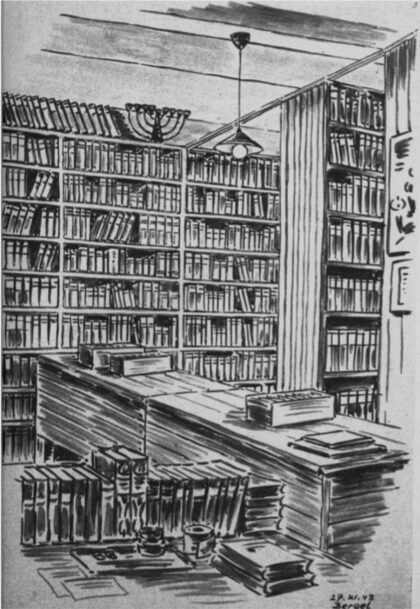

And the library of the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies? It is the only one to stay freely accessible until 1941. Many of its books are of great cultural and intellectual significance, a representation of Jewish traditions and history. And they allow people to read, to educate themselves and to research, despite the persecution. Until the very end, the library staff do their utmost to protect and care for this legacy and this place of refuge

With great talent for improvisation, Jenny Wilde and her assistant Adele Sperling keep operations running. The challenges they face are manifold: there are no funds available for new books. There are hardly any books by Jewish authors left. In addition, the production of Jewish book is banned in the 1930s. And not to be forgotten: Germany has been at war since 1939 and all German libraries are cut off from trading with foreign countries

Nevertheless, books pile up everywhere in the Institute’s library – in the reading room, in the

Not all of them are interesting for educational purposes. Jenny Wilde makes a virtue of necessity and exchanges them for more suitable publications. She sets up an “unused” section especially for this exchange material.

In 1941, the Institute is forced to sell its building and continue teaching elsewhere. The book collection presumably remains in the former premises. Anyone who wants to borrow books now has to ask the Gestapo for permission. It is not until October 1942, a few weeks after the Institute itself was forced to close, that the library is officially seized, packed up and transported to the headquarters of the Reich Security Main Office.

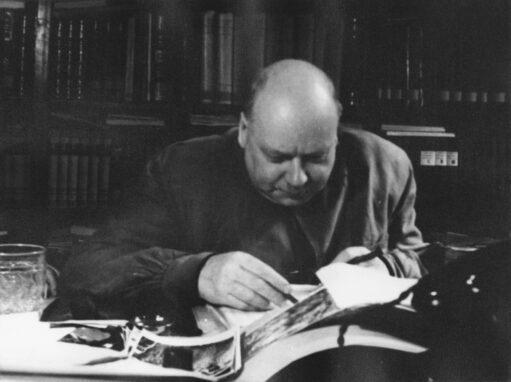

One last group photograph: lecturers, students and staff of the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies in the reading room of their library, summer 1938. In the centre of the photograph: Jenny Wilde, standing behind her: Ernst Grumach

Deportation into uncertainty

It’s over. The Institute is closed. Escape is hopeless. At the Wannsee Conference of 1942, the Nazis decide to deport and exterminate the remaining Jews. They are still trying to conceal their intention to carry out the so-called Final Solution. And so, like many others, the former employees of the Institute face being dragged into an inscrutable darkness.

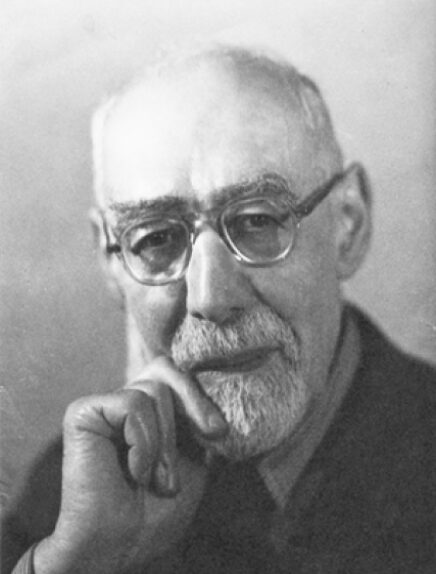

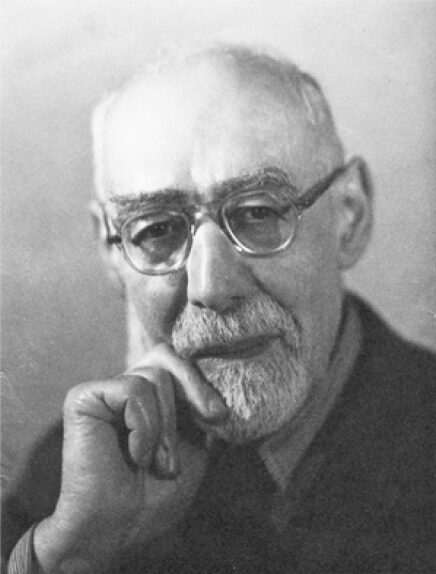

Leo Baeck is deported to Theresienstadt in January 1943. At quarter to six, there is a knock at Baeck’s door and he knows that it can only be the

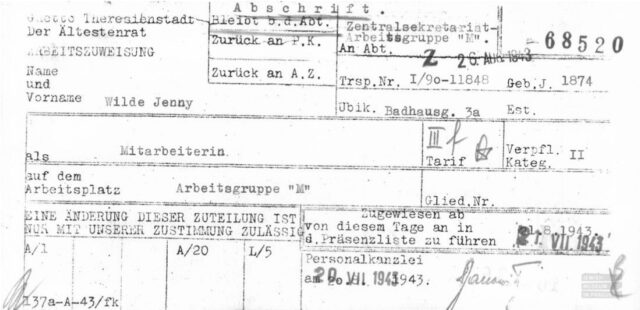

Jenny Wilde is also taken to Theresienstadt concentration camp. In February 1943, the Gestapo carries out the so-called “factory action” in Berlin. The city’s remaining Jews are arrested at their workplaces and deported. The majority of them worked for the Nazi armaments industry. Most of them are taken to

On 6 March Jenny Wilde is forced to fill out an asset declaration. Just 9 days later she is informed that her assets have been confiscated. On 17 March she is taken to Theresienstadt on a convoy of elderly people. In the former fortress, which has been built to house 3,000 people, she lives with about 40,000 other inmates. And with the fear of being transported to one of the extermination camps in the East at any time.

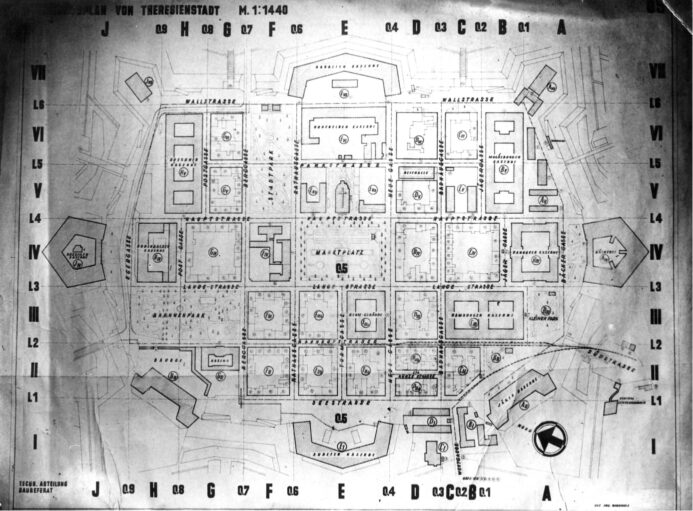

Theresienstadt

It is easy to imprison people in Theresienstadt, which was originally designed as a fortress. In 1941, the first deportees begin to arrive. Theresienstadt is an assembly camp. This means that everyone crammed together waits under terrible conditions to see whether or not they will be deported to an extermination camp. At the same time however, the Nazis also use it as a means of deception. Deportation is cynically presented to German Jews as a privilege. They are forced to sign “home purchase contracts” as if they were buying shares in a retirement home.

Following this “logic”, they have to pay for their deportation. The propaganda is intended to prevent protests from abroad, but also to keep deportees in the dark about the Nazis’ true motives. An extensive cultural programme, lectures, theatre performances and libraries, all serve to portray Theresienstadt as a normal city.

Working for the Nazis

The fate of many of those who stay at the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies until the end is forced labour. Employees of the Institute are captured by the Nazis and their skills abused.

Since 1939, the central library of the Reich Security Main Office has been flooded with books that were systematically looted from Jewish libraries, public institutions and private collections. Mountains of them pile up in the rooms of the imposing building on Eisenacher Straße. Who is supposed to keep track? The cynical counter-question is: Why not the people who are already familiar with those very books?

From 1941, Jewish forced labourers with library expertise are deployed to organise the masses of books. Because the Nazis themselves lack qualified personnel. Because the few library-trained members of the security service do not know Hebrew. And put plainly: because forced labour is cheap.

Intellectual forced labour

The fact that Jews had to contribute to the “research” against themselves is not new. From the early phases of persecution, scientists and thinkers had been obliged to perform so-called intellectual forced labour. What distinguishes “intellectual” from physical forced labour is that “intellectual forced labour” obliges scientists and artists to do work they actually love. The Jewish genealogist Jacob Jacobson, for instance, is forced to lend his expertise to the issuing of

In other places too, Jewish people are forced to join in the processing of stolen books, for example in Vilnius after the looting of the YIVO Institute, which specialises in the study of Eastern European Jewry.

The Reich Security Main Office sets up two groups of forced labourers to catalogue the stolen books: the “Grumach group” in the central library and later the “Talmud commando” in the Theresienstadt

The “Grumach group”

Its name isn’t coincidentally reminiscent of the former lecturer of the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies. Ernst Grumach is appointed as its foreman. Every morning, the group is locked in a work room by the security service to labour under armed surveillance. Officially their workday is 8.5 hours long, but actually they work for up to 16 hours. After each shift, the workers are examined. In addition to absolute secrecy, their daily work routine also comprises beatings, kicks, abuse and death threats.

For a year and a half, the “Grumach group” sorts and catalogues the seemingly endless influx of new books. According to estimates, the total stock of the “Jewish library” ultimately comprises around two to three million volumes. From the summer of 1943, the books are moved to storage to protect them from bomb damage. Ernst Grumach and his colleagues are henceforth employed to pack them up and transport them. After the looted books have been gathered together and catalogued in Berlin, within a very short time they are scattered across depots in Poland, the Czech Republic and Germany.

The “Talmud commando”

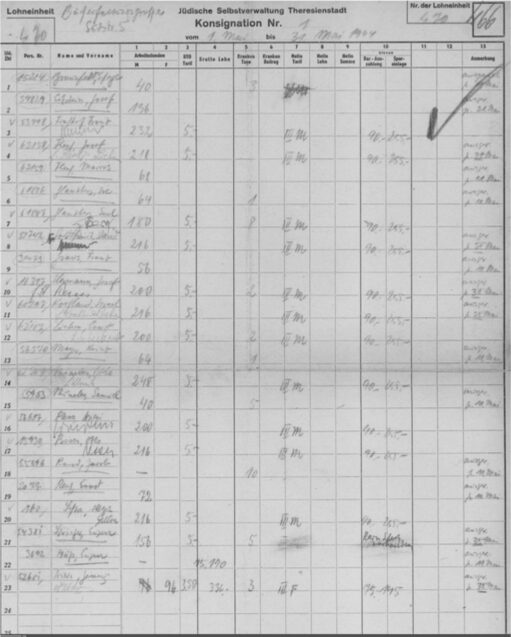

Some of the books are taken to the Theresienstadt camp to be processed. There, Jenny Wilde is part of the “Talmud commando”. In changing formations, the group catalogues books on Jewish culture and history. The work is exhausting and the pace is fast. Every single day – without breaks – the forced labourers spend eight hours squeezed into low ceilinged rooms.

After a year, the “Talmud commando” concludes its work. It has processed around 40,000 books during this period, including the cataloguing of 28,170 books in Hebrew. Of the 35 forced labourers in this group, only nine will survive, including Jenny Wilde. As a 69-year-old single woman she thus defies the sad statistics of who survives the concentration camps.

Forced labour as a refuge?

We have a pretty clear idea of forced labour, don’t we? It is an image of exploitation, of cruelty, of exhaustion. But if we broaden our perspective a little, we also see Jenny Wilde and Ernst Grumach. For both of them, forced labour is also something else: salvation. Toiling in haste, yes toiling in haste was bad, they later write, but working with the books gave them strength and hope. Some of their contemporaries will condemn them for this. But who are they to judge what helps people survive?

They had allegedly become accomplices. People who did not share Wilde’s and Grumach’s experience would later say that they had made common cause with the Nazis, albeit against their will. Let us not forget the coercion, the desire to survive and also the absurdity of their situation. Forced labourers like Jenny Wilde and Ernst Grumach were confronted with a situation that defies all logic:

“In view of the fact that under National Socialism Jewish people from all parts of Europe [were] eliminated by every conceivable means, while Jewish

were saved with thorough care, [it] must have been one of the most paradoxical experiences of their lives to be led by SS guards into a room that contained the treasures of Jewish centuries in unprecedented quantities.”(Quote shortened and edited for better readability)

(Herbert A. Strauss, 1947)

Let us not forget the difficult fates they endured. Leo Baeck was arrested in 1943 and taken to Theresienstadt. He describes the conditions in the camp as follows:

“In a space that previously housed barely 3,000 people in constrained military quarters, there were now almost 45,000 crammed together here, in barracks and other houses, huddled together, on top of one another. […] Month after month, year after year, that was the world, and the crowd swallowed up the individual. He was enclosed by the mass, just as he was enclosed in the cramped conditions and dust and dirt, in the swarms of insects, and enclosed, almost from within and from without, by the hunger that seemed never-ending – in the camp of the concentrated, never just to himself.”

(Leo Baeck, 1945)

The escape from reality into professional pride or the joy of a valuable book – all this may have given comfort to the forced library workers. They had to perform tasks that were actually close to their hearts. This dilemma too, is part of the cruelty of their captivity.

You are beginning to sense that the books were more than just bound paper. They were an escape from reality, a refuge, a salvation.

Letter from Jenny Wilde to her friend Heinrich Loewe (April 3, 1946) in which she writes about the role forced labor played for her.

How Jenny Wilde experiences forced labour

Jenny Wilde knew who benefited from her work. Yet nothing we know about the librarian suggests that this contradiction troubled her. Not a word of complaint or disgust about the fact that she was forced to participate in the processing of the books stolen by the Nazis.

On the contrary: for Jenny Wilde, the work of the “Talmud commando”, was “honourable” and a way to escape reality, even if only briefly.

In a letter dated 23 April 1946 to Heinrich Loewe, her long-time friend and mentor, she writes, among other things: “My purpose was the work that filled me and made me forget what was going on around me.” Sorting books gave her strength, an identity and a connection to her former life. In another letter to Loewe, she expresses professional pride: “[…] I [want to] repeat that I was in Theresienstadt for 3 full years and that I worked in a specialist capacity, despite the well-known conditions, hunger, hardship, all diseases. […]”

Jenny Wilde is not alone in this dichotomy: other prisoners also volunteer for the “Talmud commando”, including Leo Baeck. Fortunately, Jenny Wilde herself is not aware of the criticism. At least there is no evidence of it. Her colleague Ernst Grumach had a different experience.

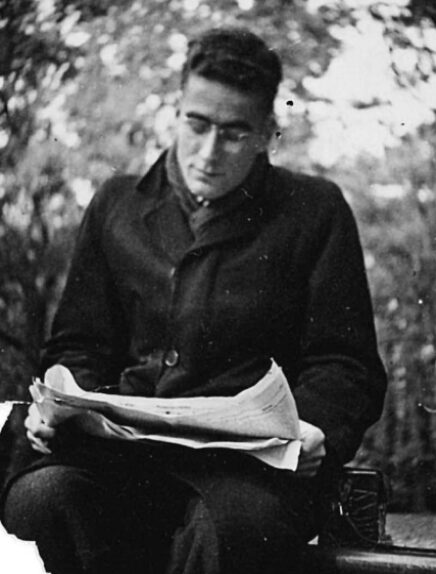

The free thoughts of Ernst Grumach

In front of Grumach’s eyes, treasures pile up in impressive heaps in the central library of the Reich Security Main Office. He turns this chaotic mass of books into a library that he describes not without pride: “[…] a Jewish library of an extent and completeness as probably nowhere else in the world” (Grumach, 1945).

Grumach hopes to contribute to “preserving the looted Jewish libraries themselves, and to rebuild and weld them together in such a way that they could one day be taken over by us as a central Jewish library, […]”.

He considers the library his work despite all circumstances. And is devastated when it goes up in flames:

In November 1943, the Reich Security Main Office library is hit by an air strike. Grumach loses the very purpose he had ascribed to his work.

“I saw my life’s work burn in November of that year, […] but I didn’t care. […] The struggle was over for me, there was no point to it any more, it was just an empty, pointless dragging along and waiting for the end.”

(Grumach to Max Wiener, 1945)

Grumach will stick to his idea of a “Central Jewish Library”, which is to be built from the holdings looted by the Nazis. Even his friends do not understand him. Take over a library looted by the Nazis? Profit from the Nazi theft? And a Jewish library on German soil? All these may have been moral dilemmas to which there was no easy answer.

However one may judge the idea of his library, the fact that amidst all of this duress he allowed himself to take pleasure in it should be seen less as a weakness than as proof of mental strength: a survival strategy built on stacks of books.

Scattered, destroyed, lost?

Of course, the National Socialists would have liked to gain possession of all valuable books from Jewish libraries. But their plan failed, also because of the courageous people, who risked a great deal to bring the books to safety. The Higher Institute for Jewish Studies also contributed to such rescue operations.

Join the symbolic resistance!

The Institute’s staff are aware that their books could fall victim to Nazi robbery or vandalism at any time. That is why they devise a plan. Particularly valuable books and documents are to leave the country together with trusted people. If the books are made to look as if they are part of their private libraries, customs could easily overlook them. The risk will be even lower if the person travelling abroad does not have a German passport. And indeed it works. The Hungarian professor of Talmudic studies, Alexander Guttmann, leaves Germany in 1940, taking the 60 most valuable works of the Institute to Cincinnati with him.

A year earlier, acting with wise foresight, the Institute succeeds in sending three boxes of material to Jerusalem. They contain the very valuable academic papers of the German psychologist Moritz Lazarus.

But even outside the Institute’s walls people are courageously working to protect Jewish cultural assets. For example at the

These and other rescue actions are acts of symbolic resistance against the attempt to eradicate everything Jewish from Europe.

“The symbolic act of rescuing books when perhaps people themselves were no longer able to be rescued or to rescue themselves is perhaps a final act of spiritual resistance against the nazi oppressor.”

(Dr. Noah S. Gerber, 2023, Tel-Aviv University)

Escaped

And what about the people? Let’s turn briefly to the members of the Institute who managed to emigrate. There is a great sense of relief when you read this, isn’t there? But it wasn’t easy for them, and they made it even harder for themselves.

Ismar Elbogen, for example, refuses to consider emigration for a long time. He tells his wife that he still has duties to fulfil. From 1937 onwards, he no longer feels this way. All he can really do now is advise students on where to emigrate. He himself goes to the USA and hopes to be able to help other colleagues and students leave Germany from there.

Elbogen’s wife describes his departure from the Institute as a painful one:

“[…] I can never forget the deeply serious, painful expression on his face when he took the podium to speak at his farewell ceremony. […] the auditorium was packed; for even though many had already left, new ones kept on arriving, the number had not diminished. I have pictures of the ceremony, during which there was an almost holy atmosphere, the podium decorated with flowers, the seriousness of all the young faces, the imminent separation, – it made quite an impression!” (Regina Elbogen, 1956).

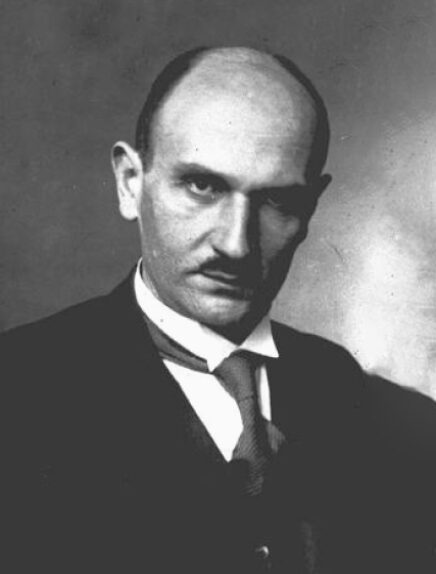

Farewell ceremony: Ismar Elbogen stands on the podium and gives a last speech, Leo Baeck sits in the audience and listens.

South America

CHE

ISR

USA

Abraham Heschel

Alexander Guttmann

Max Wiener

Franz Landsberger

Eugen Täubler

Franz Rosenthal

...

Julius Galliner

Emil Bernhard-Cohn

Max Wiener

Fritz Bamberger

Herbert A. Strauss

...

UK

Malvin Warschauer

Max Eschelbacher

Jenny Doerfler

...

ARG

Hugo Fuchs

Fritz L. Steinthal

Suse Hallenstein

...

BR

AUS

Perished

But you also know that very few got away. Many members of the Institute did not survive the Holocaust. In the Library of Lost Books, a memorial is dedicated to them.

Do you still remember Regina Jonas? After the November pogrom, the progressive rabbi mainly took care of old people in the Jewish hospital in Berlin. In the winter of 1940/41, she acts as a rabbi for communities that no longer have one.

In 1942 she is deported to Theresienstadt together with her mother. Here, too, she works as a rabbi. In 1944 she is sent to Auschwitz and presumably murdered on the day of her arrival.

An incomplete list of graduates and employees of the university who were killed by the Nazis:

“Of the professors who signed my diploma between the summer semester of 1939 and the summer semester of 1942, of the teachers who took the place of those who had emigrated, and of the seven community functionaries hired as guest lecturers in 1940, only Leo Baeck, Ernst Grumach, Alexander Guttmann, Eugen Täubler, Moritz Henschel and Leo Wisten survived the war in Berlin, emigrated or returned from concentration camps. The others perished miserably in the concentration camp, disappeared without a trace following their deportation from Berlin to Eastern Europe, or were executed without a trial.”

Herbert A. Strauss, Student der Hochschule

Survived

In May 1945 the war is over. Prisoners of war, concentration camp inmates and forced labourers are liberated. We have been following some of the Institute’s people so closely, that you are surely asking yourself whether they were among the freed.

Artefacts of destinies

Where the books are, human tragedies have taken place. People have been murdered. People have fled. People have survived. The books are silent witnesses to these destinies. But they can tell us a lot if we follow their trail. And know how to read them.